Supplier Quality Management - A Guide

Supplier Quality Management

Supplier Quality Management (SQM) or Supplier Quality Management represents the set of activities and processes required to ensure consistent product quality across the entire supply chain - from raw materials to the finished product delivered to the final customer.

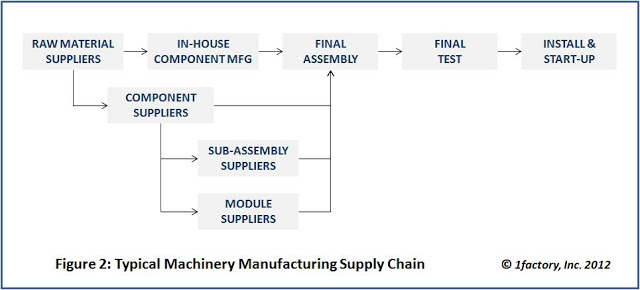

The Supply Chain itself, is a series of interlinked processes from purchasing of raw materials, through the completion, delivery and installation of a finished product for an end-user. All intermediate operations such as machining, assembling, testing, shipping, distribution, install & start-up, along with the suppliers, logistics providers, distributors, and retailers that provide the required parts and services, and your own manufacturing plants, are elements of the supply chain.

Example: Supply Chain for Machinery Manufacturing

Challenges in Supplier Quality Management

Supply Chain Complexity

Supply Chain Complexity is a function of many variables, such as, number of products, number of product variants, number of parts, number of bill of material levels, make vs. buy decisions, number of suppliers, number of supplier tiers, geographic distribution of design and manufacturing locations, and number of specialized processes.

Through the early 1990s, supply chains were relatively simple, supporting the mass-production of a limited range of products, with a significant portion of each product being manufactured in-house.

Since then, in response to evolving market conditions, product and supply chain complexity has grown exponentially. Mass-production, in some cases, has been replaced by mass-customization, and in-house manufacturing has been replaced by a multi-tiered, highly specialized, globally-distributed supply chain. Manufacturing capabilities that were previously under one roof are now spread across multiple tiers of the supply chain.

Impact of Complexity on Quality

In this new structure, Tier-0 firms have a limited understanding and almost no visibility into the detailed manufacturing processes through the supply chain, while firms at lower levels on the supply chain have limited visibility to the context in which the final customer uses the product, and as a result may not understand the importance of requested design features.

As supply chain complexity increases, the ability of a firm to control manufacturing processes across the supply chain diminishes. As a result, a large portion of total defects now originate in the supply chain. In fact, there is a direct correlation between supply chain complexity and the number of defects observed in a product.

Supply Chain Complexity is the biggest challenge for supplier quality management and cannot be handled by simply adding more people to your supplier quality organization. Your business processes and IT systems need to be transformed to meet this challenge head on.

A Framework for Supplier Quality Management

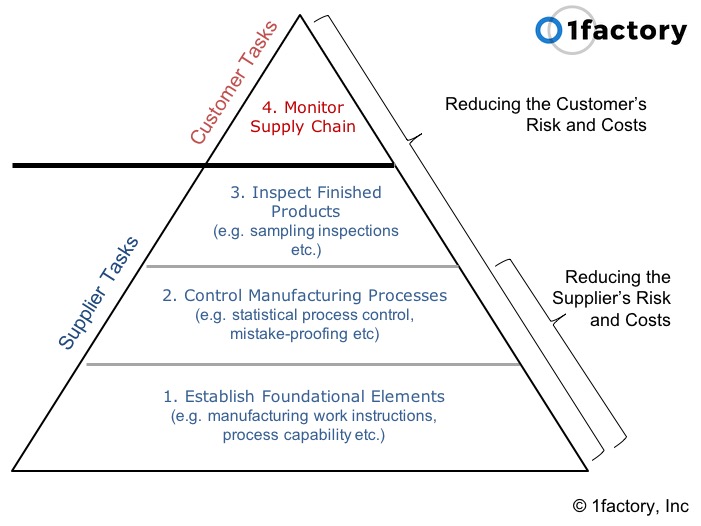

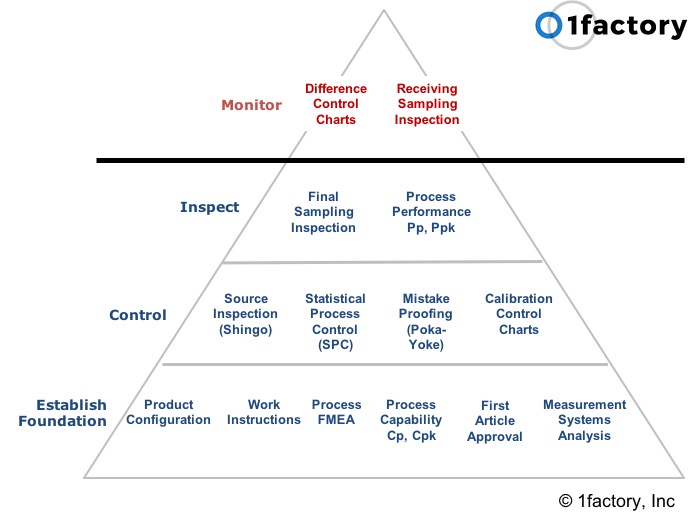

The 1factory Supplier Quality Management Framework© groups the required controls into 4 sets of activities:

- Establish Foundational Processes

- Control of Manufacturing Processes

- Inspect Finished Products

- Monitor & Improving Supplier Performance

As a buyer of parts (or as a supplier quality engineer), you must verify the existence of the first three groups of controls - Foundational Processes, Process Control, and Inspection - at each supplier for each part.

In addition, you will need to establish a continuous monitoring mechanism to ensure that the controls established at each supplier are working effectively.

Controls related to inspection and monitoring benefit the buyer by reducing the possibility of a defective part entering the buyer's factory or reaching the end customer.

On the other hand robust foundational processes and process control benefit both the supplier and the buyer. The supplier benefits by preventing defects and therefore avoiding the costs associated with inspections, rework, scrap, lost capacity, customer escalations, returns etc.

In addition, these costs are invariably transferred to the buyer, and the buyer faces both increased risk of defective parts and increased costs in the absence of foundational processes and process control. In an average machine shop these costs run as high as 7% of revenue and represent a huge opportunity for improving profitability at the supplier and reducing costs for the buyer.

Therefore, while Inspection related controls form the "minimum acceptable" set of controls for a buyer, it is essential for a buyer and supplier to work together on the Foundational and Process Control elements to ensure a lower total cost for both buyer and supplier.

1. Foundational Processes

Robust foundational processes benefit both suppliers and buyers by preventing defects and reducing associated costs. Effective change control systems manage engineering changes, document revisions, and process modifications.

Preventive maintenance programs ensure equipment reliability through scheduled maintenance, calibration, and breakdown prevention.

Production readiness verification through setup verification, first piece inspection, and process parameter validation ensures consistent quality from the first part.

Detailed work instructions with visual aids, critical parameter identification, and quality check points provide clarity for operators.

2. Control of Manufacturing Processes

Effective process control ensures consistent quality output and reduces variation in product characteristics. Statistical Process Control (SPC) enables monitoring of critical characteristics, implementation of control charts, analysis of process capability, and reduction of variation. In-process quality checks at strategic inspection points with defined measurement methods and sampling plans catch issues early.

Environmental control measures for temperature, humidity, contamination prevention, and material handling protect product integrity throughout the manufacturing process.

3. Finished Product Quality Assurance

Final product inspection ensures that only conforming products are shipped to customers. Comprehensive inspection planning identifies feature verification requirements, measurement methods, sampling plans, and acceptance criteria focusing particularly on special characteristics.

Quality data management systems enable effective collection, analysis, reporting, and traceability of quality information to support improvement activities and provide evidence of conformity.

4. Performance Measurement and Improvement

Continuous monitoring and improvement of supplier performance ensures long-term quality success. Supplier scorecards tracking quality metrics, delivery performance, cost management, responsiveness, and improvement initiatives provide visibility into overall supplier health.

Quality system audits verify compliance with requirements and identify improvement opportunities. Corrective action management systems ensure that quality issues are properly addressed through root cause analysis, containment actions, corrective measure implementation, and verification of effectiveness.

Supplier Quality (Part and Parameter Level) vs. Supplier Development (Business Process Level)

In general, there are two elements to Supplier Quality Management. The first element focuses on individual Part Numbers and the related parameters, making corrections and improvements to manufacturing processes and quality control methods to fix and prevent problems. This team ensures that parts coming in from suppliers, meet specifications, and that you can continue to ship finished products out to your customers. The payback on these efforts is usually in the short term. Supplier Quality activities are supported by a contractual obligation on the part of the supplier to ensure only conforming parts are shipped.

The second element, focuses on the business process level, to ensure that both your supplier (on whom you depend) and you, continue to be successful in the long run. Supplier Development may not have a contractual basis and instead requires a collaborative relationship between buyer and supplier. Supplier development programs begin with a mutual recognition of dependence, and a commitment of support by executives at both buyer and supplier.

Building Supplier Capabilities

You do not need to, and nor should you attempt to develop all of your suppliers. Instead, you need to identify the subset of suppliers that makes critical components and cannot be easily replaced due to a technical or a capital investment barrier. Next, you need to identify one or more areas for improvement. Most companies measure suppliers on Quality, Cost, and Delivery. To improve these outcomes, we need to focus our efforts on building the suppliers capabilities in multiple areas. Here are some examples:

- Capacity: On-time delivery is a function of capacity, yield, and shop-loading. Many small suppliers view capacity as a function of how many shifts they run, and how many machines they operate, while ignoring efficiency and yield. A buyer can usually help by teaching the supplier the basics of lean manufacturing and guiding the supplier through a set-up and cycle-time reduction process or a yield-improvement process, which free up capacity, without the need for adding shifts or equipment.

- Change Control: One of the most common root-causes for defects is inadequate change control at suppliers. When a buyer provides a new drawing or revision, how does the supplier ensure that the old drawing, the old fixtures, the old CNC code, the old quality control plans are all updated? Similarly, when a supplier makes a component substitution or change, how does he communicate the change?

- Inventory Control: Many suppliers, both small and large, do not have robust inventory controls in place. As a consequence, parts are everywhere in the shop, and raw, WIP, and finished products are intermingled. Worse, defective parts are right next to good parts, and mix-ups occur frequently. Simple 5S efforts can go a long way in preventing these issues.

- Sub-tier Supplier Management: Most suppliers can barely get their own quality control work done. They definitely don't have the resources to control their sub-tier suppliers. When sub-tier suppliers play a critical role (for example: cleaning, packaging, or anodizing etc.), your supplier will need help in developing a sub-tier supplier management process.

- Data Analysis: One of the parts we purchased involved a heater element attached to an aluminum plate. The resulting temperature uniformity across the plate was critical to the performance of our equipment. When a customer reported a problem with uniformity, we scrambled to find data and characterize (after-the-fact) the temperature distribution. It was difficult to pinpoint by then whether the problem came from the heater element or the attachment process. For complex components and manufacturing processes like these, you want to help your supplier establish data collection systems and teach them how to analyze and act on the data collected. In situations like these, you are only going to be as successful as the weakest link in your supply chain.

- Training: Developing the supplier's human resources, also falls within the scope of supplier development. As an example, machining suppliers may benefit from technical courses for GD&T, and packaging, sterilization, and cleaning standards etc.

Alignment of Objectives

Before you can begin a supplier development process, your supplier will need to acknowledge the need for improvement, and commit resources and management support for the project.

Your Supplier Development team will also require internal support from your Supply Chain and Sourcing teams. The support of the Head of Purchasing, and the Supply Chain / Sourcing Manager responsible for the commodity must be engaged and committed to a longer-term vision, to ensure that tactical challenges around cost reduction don't disrupt the strategic efforts around capability development.

It is also important to consider how strong this capability is within your own organization. Can you truly add value to your supplier, or are you disrupting their operations? We have seen attempts to implement lean at suppliers often fail because the buyer's own understanding of lean is very weak, and their own operations are poorly run.

The Long-Term View

And finally, always take the longer-term view. Don't waste your time worrying about how to split the benefits from the development efforts. Recognize that if your supplier's performance improves, you save money. For example, if the supplier improves quality, his yield improves, and you save money from fewer inspections and fewer defects. Similarly, if your supplier's capacity is freed-up, his on-time delivery to your factories will improve, making your production smoother and more predictable.